Please click here to view full 2019 ROFFS™ Bahamas Season Fishing Forecast as a PDF.

Bahamas Season Fishing Forecast for 2019: GREAT FISHING ACTION THIS SEASON IN BAHAMAS

By Daniel C. Westhaver

Introduction:

Since 2003, oceanographers at ROFFS™ have been developing objective methods for forecasting the overall fishing conditions during the spring Bahamas tournaments from April through early June. The hypothesis for forecasting the seasonal marlin fishing action stems from the location of the blue and often warmer water that occurs from the Cat Island – San Salvador Island area and south to southeast of these islands where it is presumed that the marlin concentrate before, during, and after spawning. We have been calling this water “blue marlin water” in our analyses. From satellite data, it is relatively easy to identify this water based on its optical signature and surface water temperature characteristics. Our working hypothesis and experience have shown that the marlin are associated with this water and the more “blue marlin water” that exists in the Abaco Islands and Eleuthera Island areas, the greater the relative apparent abundance of marlin in these areas.

In recent years we have also observed an association between the “blue marlin water” and the yellowfin tuna action in the Bahamas, northward along the western side of the Gulf Stream between Jacksonville, Florida and towards Cape Hatteras, North Carolina. We do observe evidence that when more “blue marlin water” passes northwest of Abaco to the eastern side of the Gulf Stream that a certain unknown proportion of the migratory fish move to the western side of the Gulf Stream. This brings more fish to the coastal fisheries at the edges of the Gulf Stream water throughout the spring to early summer season.

Based on our observations in the Bahamas from Eleuthera to the Abacos over the last 20+ years, it appears that excellent fishing action occurs within the Bahamas tournament areas when there is a substantial volume of the “blue marlin water” pushing over the 100 fathom (600 feet) and shallower ledges along the eastern side of Eleuthera and the Abacos. Relatively favorable fishing seasons occur when this water only occurs over the 500-1000 fathom depths, but does not reach the 100 fathom or shallower depths of both areas. Mediocre years occur when there is a lack of this water over these areas. However, short pulses of this water bring fish into these areas. Unless there is a sustainable flow of the water into these regions, the catch rates remain below average to average through the season. It is also important to understand that good fishing action on a daily basis is linked to the water mass boundaries created by these currents, and where they are stable for consecutive days over good bottom structure and ledges. These features, that have remained favorable for multiple days, concentrate the baitfish and draw bigger fish into these areas.

The hypothesis is also based on our experience using the hourly satellite observations of the ocean conditions derived by ROFFS™ (roffs.com), catch reports provided by a variety of sources for the past 30 years, and data derived from other sources of data such as drifting buoys, gliders, aircraft, private boats, and satellite altimeters. The infrared (IR) satellite data are used to observe the sea surface temperature (SST) and the ocean color data are used for indices of phytoplankton (chlorophyll), water clarity, and colorized dissolved organic material are received from a variety of data sources including NASA, NOAA, Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership (SNPP or JPSS), and the European Space Agency (ESA) satellites. The altimeter data only provides a low-resolution look at conditions with a time delay (5-10 days to produce usable large scale circulation models) that limits the data’s utility related to high resolution and real-time operational oceanography. While the ocean changes significantly over such short periods, the altimeter data can be used for an overall view of the ocean’s surface circulation. It is not typically useful for evaluating small scale, short-term (daily) changes in the ocean currents or their boundaries that control the location of the fish.

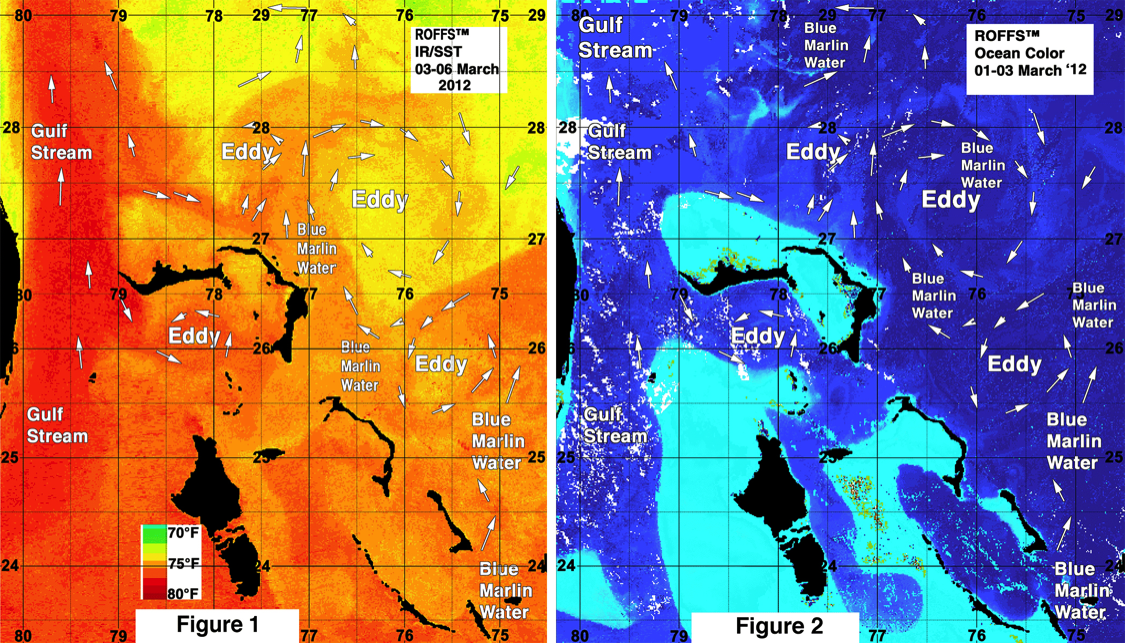

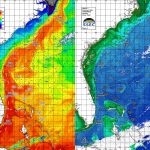

Figure 1: shows an infrared (IR) derived sea surface temperature (SST) image derived using NOAA and NASA imagery over the 03-06 March 2012 period. Figure 2: shows an ocean color image derived over 01-03 March 2012 using NASA imagery. Arrows point the direction of currents. Important features are labeled.

During the last several years we had observed that the conditions over the Bahamas tournament areas were favorable as early as January, February and March in terms of the presence of “blue marlin water” off Abaco and Eleuthera (Figures 1 & 2). As stated earlier, the aspect for having a good blue marlin season is the presence of the “blue marlin” water pushing over the 100 fathom (~ 600ft) ledge or the bank and good bottom structure and canyon areas creating persistent convergence zones for baitfish to concentrate.

Figures 1 and 2 show the distribution of the “blue marlin water” prior to the 2012 Bahamas spring tournament season. Clouds prevented us from providing an exact match in time due to the clouds associated with the strong cold front that stalled over the Bahamas during this time period, as the satellites cannot observe the ocean conditions through the clouds. However, using a variety of computer techniques ROFFS™ was able to remove cloud artifacts to allow a one-day overlap of the imagery and provide a better comparison. The darker blue water is the “blue marlin water”

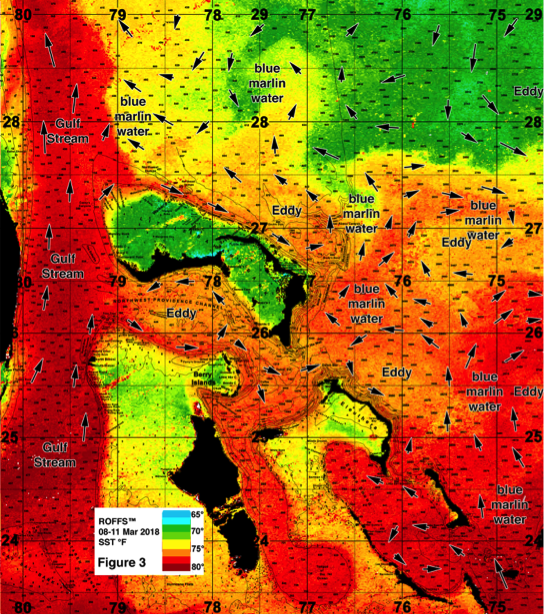

During the actual 2011 through 2016 Bahamas tournament fishing seasons the “blue marlin water” existed in the tournament areas, only to be pulled away from the tournament area by the ocean currents forced by various eddy features (60-120 miles in diameter) that occurred east and northeast of Abaco. Some good fishing action happened during these years due to the intermittent pulses of the “blue marlin water” and the presumed migration of the fish through the area. However, during tournament times in April, May and June most of this “blue marlin” water was pulled north and northeast, as has been the trend over those years. However, in 2017, the arrival of the “blue marlin” water east of Abaco almost to the 100-500 fathom contours and north of Walker’s Cay by mid-March was located farther to the northwest and north of Abaco, and the west to northwest push of this warmer darker “blue marlin water” continued to drift toward the Gulf Stream, which resulted in an earlier than normal pulse of marlin and tuna to the northern Bahamas areas. In April and May 2017, “blue marlin water” was held into the ledges from between Eleuthera and Abaco by consecutive clockwise rotating eddy features east of Cat Island and Eleuthera providing good marlin and tuna action for the majority of the season. However, last year (2018), the initial “blue marlin water” push into Abaco and Eleuthera that existed early in the season (Figure 3 and 4), did not continue into late March, and as the “blue marlin water” got pulled back offshore of the Islands, the tuna and marlin action in April, May and June was not as productive, except for some days of good action due to intermittent pulses of the “ blue marlin water”.

[one_half][responsive] [/responsive][/one_half] [one_half_last][responsive]

[/responsive][/one_half] [one_half_last][responsive] [/responsive][/one_half_last]

[/responsive][/one_half_last]

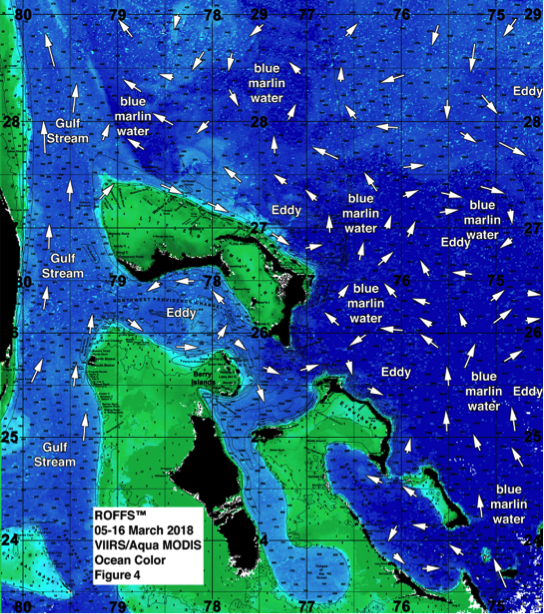

Figure 3: Last years conditions were derived from a variety of infrared sensors to get SST from NASA, NOAA, and JPSS satellites during March 08-11, 2018 and Figure 4: was derived from the ocean color/chlorophyll imagery during March 05-16, 2018 from the VIIRS sensors on SNPP satellite in combination with the Aqua sensor on the MODIS satellite supplied by the University of Delaware. We consider this an image pair.

Background and Some Data for 2019

Although we have learned that the favorable oceanographic conditions develop from the presence or absence of the “blue marlin water” during the main tournament season, we continue to prepare the annual forecast from data around early-to-mid March. These allow us insight into the conditions prior to the tournament season, and understand the ongoing fishing success starting in March through June. One challenge of producing such an early forecast is that conditions are likely to change significantly from one fishing event to the next without any proven and field-tested methods to predict the changes over the period from March through June. Despite what you may have been told through non-scientific means, there still are no reliable numerical oceanographic models that make accurate and reliable high resolution localized oceanographic forecasts for short-term or long-term fish finding applications. ROFFS™ continues to work with other oceanographers to improve, test and validate ocean and climate models, but as of now, they continue to be less accurate than you would believe.

For forecasting short-term oceanographic conditions related to finding fish, ROFFS™ believes that the conditions observed on any given day are the ones likely to continue into the short-term future (24 hours). While getting larger scale low-resolution interpretations of conditions using altimeter or models, we prefer to use real-time observations and have learned that evaluating the preseason conditions annually provides insight into future seasonal trends. Experience is our greatest asset. For the spring Bahamas tournament season we derive our first indications of the ocean conditions during the first two weeks in March. We evaluate whether or not we are observing “normal” (climatologically mean conditions) or anomalies. We rely on real time satellite data but use climate models from some of the world experts in the field. One indication is sea surface temperature (SST) in the core of the Gulf Stream off Miami and the SST of the Bahamas blue marlin water east of Cat Island to east of Long Island. Because we started our forecasting studies during the first week of March in 2003 we have continued our time series using that week to directly compare each year.

The ROFFS™ 16 year (2003-2018) mean SST for the core of the Gulf Stream off Miami is 78.6°F during our standard early to mid-March measurement period. The SST has been as low as 74.8°F (2009) to a high of 80.5°F (2007) and still have not observed any overall trends as of yet. This year the SST was 80.1°F in the core of the Gulf Stream off of Miami on March 07-11 (2019), which is similar to the same period as in 2017 and warmer than the 16-year mean. While we have not been recording the SST of the Bahamas “blue marlin” water offshore of Cat Island to Long Island as long, the 11 year mean (2008 – 2018) SST for the warmer water east of Cat Island area is 77.0°F. This year the SST of the “blue marlin” water east of Cat Island/Long Island was 78.9°F during the standard early to mid-March time period. The water both off Cat Island and within the Gulf Stream east of Miami both increased over last year. Although we continue to observe this variability and no real consistent trends, the presence of the warmer water and “blue marlin water” off Cat Island could again indicate an earlier than normal arrival of marlin and various tuna species into the Bahamas region and farther north.

The global, hemispheric and especially the regional climate models provide guidance into the present and future conditions. We usually use the oceanographic models, climate data, analyses, and forecasts provided by Columbia University’s International Research Institute (IRI) for Climate and Society (https://iri.columbia.edu), NOAA’s Climate Prediction website (http://www.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov), the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/about), as well as advice from our colleagues at NOAA’s Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/), the University of Miami’s Cooperative Institute for Marine and Atmospheric Studies (CIMAS http://cimas.rsmas.miami.edu/) and North Carolina State University (http://omgsrv1.meas.ncsu.edu:8080/CNAPS/atm.jsp). We also use catch data from a variety of public and private sources. Based on the 2019 IRI multi-model probability forecast, the precipitation is expected to exceed climatological mean or “normal” conditions over the April-May-June period. As what happened over the past two years, air temperatures are likely to be warmer from April through September and SST is forecasted to be slightly above the mean in the Bahamas Islands area. This suggests that the “blue marlin water” is already producing fish this season, and the main population of marlin are likely to arrive earlier than normal due to the slightly higher water temperatures compared to the same time last year, and the likely arrival of marlin to the northern Bahamas area will occur at earlier seasonal times along with the influx of the warmer “blue marlin water”.

As we continue to monitor and learn more about climate variability and ocean-wide circulation we considered other indices such as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO) and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation (AMO). Without going into detail the NAO is the dominant mode of winter climate variability in the North Atlantic region ranging from central North America to Europe and much into Northern Asia. The NAO is a large-scale variation in atmospheric mass between the subtropical high and the polar low. The corresponding index varies from year to year, but also exhibits a tendency to remain in one phase for intervals lasting several years. The NAO is a climatic phenomenon in the North Atlantic Ocean defined as the difference of atmospheric pressure at sea level between the Icelandic low and the Azores high. Through east-west oscillation motions of the Icelandic low and the Azores high, it controls the strength and direction of westerly winds, currents, and storm tracks across the North Atlantic Ocean. It is part of the Arctic oscillation, and varies over time with no particular periodicity. It appears to be one of the most important manifestations of climate fluctuations in the North Atlantic and surrounding humid climates (see Wikipedia and the previously listed web links for more details). The NAO 2018 index for January and February 2018 was 1.44 and 1.58 respectively, above normal. This year (2019) the NAO index for January and February is 0.59 and 0.29 respectively, which is lower compared to last year, but is still considered normal to above normal. We continue to remain uncertain what the implications are for water current velocity (speed and direction), ocean eddy generation and movements, as the effects of NAO in the Bahamas area is not obvious. Typically the NAO is more important for driving the west to east winds (westerly’s) north of 30°N latitude (mostly 45°-65°N). An increase in the NAO means that the Icelandic low gets lower and the Azores high gets higher creating a stronger atmospheric gradient between the two which results in stronger winds from the west that essentially acts to cool the North Atlantic Ocean overall. A decrease in NAO index suggests less wind and warming. To understand the significance to the trends in the North Atlantic Ocean SST one has to consider the entire year, as well as, several years and decades of data. This is beyond the scope of this article.

The Atlantic Multi-decadal Oscillation (AMO) has been identified by some as a coherent mode of natural variability occurring in the North Atlantic Ocean with an estimated period of 60-80 years. It is based upon the average anomalies of sea surface temperatures (SST) in the North Atlantic basin, typically over 0°- 80°N latitude. (https://climatedataguide.ucar.edu/climate-data/atlantic-multi-decadal-oscillation-amo). The unsmoothed AMO Index for January and February 2017 was 0.233 and 0.234 respectively. In 2018 the January and February values were 0.172 and 0.062 and in 2019 they were approximately -0.060 and -0.015 respectively.

We have learned that the negative trend in these indices suggest an increase in speeds of the North Atlantic Ocean Circulation is occurring. This includes an increase in current speeds of the Gulf Stream system. The exact rate of increased speeds is unknown and the impact on Gulf Stream intrusion into the Gulf of Mexico (Loop Current), as well as, the resulting meanders and eddy formation is yet to be shown, although we have already observed some changes. Also, a negative AMO is usually associated with a decrease in the number of tropical storms that mature into hurricanes because the overall North Atlantic Ocean SST is lower (i.e., lower anomalies). This does not take into account the wind shear variability and other aspects of tropical storm genesis. For easy to understand answers to frequently asked questions about the AMO see http://www.aoml.noaa.gov/phod/amo_faq.php#faq_2.

Regarding El Niño we have yet to see or read about any direct relationship between El Niño – La Niña and the Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and the oceanographic conditions in the Bahamas area. Currently we are in a weak to moderate El Nino phase that will likely continue through 2019 (https://iri.columbia.edu/our-expertise/climate/forecasts/enso/current/). However, we continue to monitor the conditions closely. We will continue to investigate the relationship between the North Atlantic Ocean climate and the oceanographic conditions in the Bahamas in the future. But we included this information to spark your interest in climate indices.

Nowcast Analysis

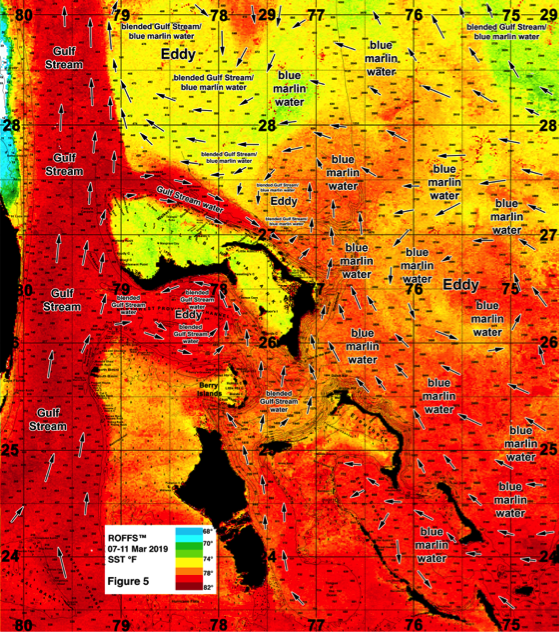

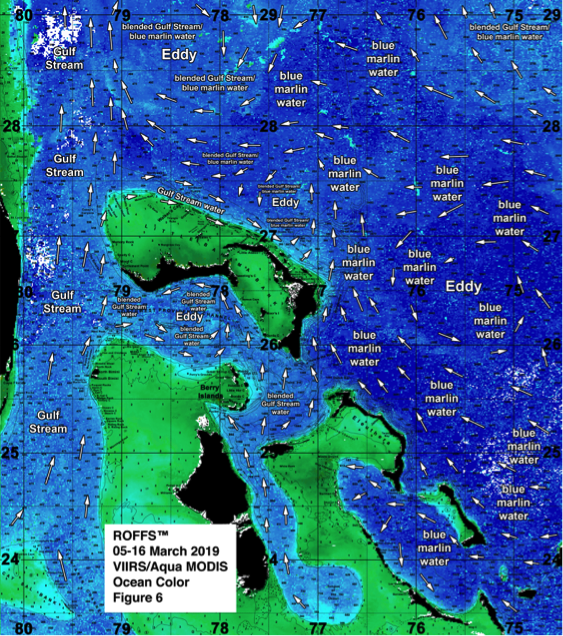

In this section we want to discuss and show you the current oceanographic conditions (Figure 5 and Figure 6) and compare it briefly to last years conditions (Figure 3 and 4). For clarification purposes Figures 3 and 5 were derived from a variety of U.S. (NASA, NOAA, JPSS) satellites during the early to mid-March (March 07-11) period and Figures 4 and 6 were derived from the U.S. SNPP VIIRS and NASA MODIS Aqua ocean color/chlorophyll imagery during relatively same early to mid-March time period (March 05-16). The exact values of the original data from different satellite sensors are not the same but we cross-calibrated the imagery so that the signature and values of the “blue marlin water” is consistent over the histories of the satellites.

In both instances, we could not use single and same day imagery for the SST and ocean color data due to cloud cover interference, so we used a combination of imagery and the ROFFS™ cloud reduction techniques to produce these relatively cloud-free images. However, for comparison purposes we consider these images as an equal image pair for the purposes of this discussion. While these provide a visualization of the pre-season March conditions, they also provide examples of how the eddy features are pulling the “blue marlin water” in different directions. This is important for understanding the dynamics of the region. Both images for each year have the same arrows, eddy and “blue marlin water” labeling. The flow of the water was derived from our ROFFS™ sequential image analysis of Lagrangian coherent features where we study several days of satellite imagery to follow the signature water masses and their motion. An example of this years SST satellite infrared imagery can be found on the ROFFS™ website at (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kknh4G3DPuc) showing the flow of the water around the Bahamas region during the last two months, where the darker grey water represents the warmer water.

This year’s indicator conditions are shown in Figure 5 and 6. Currently, there are only two obvious influencing clockwise and counterclockwise circulations that are rotating at different speeds and drifting in different directions at differing rates, considerably less eddy features than we have observed during the same time last year. Due to size and space constraints we are not showing the substantial volume of the bluer “blue marlin water” farther east of Eleuthera and Cat Island here, but one can see it in the video referenced above (typically darker grey signature). Overall, as you can see in the ocean color image (Figure 6), there are already large amounts of “blue marlin water” pushing in a favorable direction over 100-500 fathoms surrounding Cat Island, east of Eleuthera, southeastern Abaco Island, and in 500-1000 fathoms northeast of Abaco Islands and into the Great and Little Abaco Canyon areas for promising early season marlin action similar to the past two years.

[one_half][responsive] [/responsive][/one_half] [one_half_last][responsive]

[/responsive][/one_half] [one_half_last][responsive] [/responsive][/one_half_last]

[/responsive][/one_half_last]

Figure 5: This years conditions were derived from a variety of infrared sensors to get SST from NASA, NOAA, and JPSS satellites during March 07-11, 2019 and Figure 6: Derived from the ocean color/chlorophyll imagery during March 05-16, 2019 from the VIIRS sensors on SNPP satellite in combination with the Aqua sensor on the MODIS satellite supplied by the University of Delaware. Although we needed a larger date range to provide a clear ocean color/chlorophyll image, we consider this an image pair.

Furthermore, similar to the excellent preseason conditions in 2017, we are able to observe “blue marlin water” northwest and north of Abaco Island into Walkers Canyon and being carried towards the eastern side of the Gulf Stream. This could mean the arrival of and earlier than normal marlin and tuna to the northern Bahamas areas and farther north within the Gulf Stream along the coast from Cape Canaveral to off Cape Hatteras as the temperatures continue to warm.

Overall there are two main eddies we need to continue to monitor east of the Bahamas. The first eddy is turning clockwise, and located just east of the Bahamas chart (viewable online via YouTube link above) east of Eleuthera centered near 73°00’W & 25°30’N. This larger offshore eddy is pulling the majority of the “blue marlin water” west-northwest into 100-500 fathoms of Salvador, Cat Island, and Eleuthera before moving slowly towards southern Abaco Island, Little Abaco Canyon and Great Abaco Canyon. This eddy is the driving force that has feed the majority of the “blue marlin water” northward into the ledges providing good fishing conditions off Abaco and Eleuthera early this season. The second eddy is smaller and not as organized as the first, and is located in 2000-3000 fathoms east of Abaco with a counterclockwise rotation centered near 75°20’W & 26°30’N. If these eddy features remain relatively stable or move northward to northwestward, they will continue to provide EXCELLENT conditions by pulling and feeding the “blue marlin water” closer to the coasts of Eleuthera, Abaco, and the rest of the northern Bahamas for good to excellent April and May fishing. However, if these eddies drift east-northeast then the conditions may not be as favorable keeping the “blue marlin water” off the coast suggesting the favorable conditions may be farther offshore. It remains to be seen what will happen.

The ocean color image shows darker blue water compared with the Gulf Stream water. The darkest blue water in Figure 6 shows the water that likely has the greatest abundance of the marlin and is a darker blue than the Gulf Stream water along the Florida east coast and water south of Grand Bahama Island. The “blue marlin water” is slightly warmer overall than last year, and there has already been wahoo, mahi and yellowfin tuna caught in northern Eleuthera, off the Berry Islands, and south off Chub Cay. However, weather has influenced slower than normal marlin catch in recent weeks in the Bahamas. The SST of the “blue marlin water” ranges between 74.8°F to 78.9°F right now and as you can see in Figure 5 and 6, there is plenty of “blue marlin water” east of Cat Island, east of Eleuthera Island over the bank and also east and north of Abaco over the 100-1000 fathom depths.

As the water warms in the coming weeks and as these eddies east of Abaco and Eleuthera hopefully move northward, we anticipate that a substantial amount of marlin, tuna and other species will continue to be moved into the Bahamas. These present conditions are considered good to excellent pre-season conditions, which is promising for the next month or two. Our hope for the Bahamas marlin fishing action is that the temperatures are near or warmer than the mean and that these fish and the conditions will remain favorable into June like it was in 2017. However, one should note that there is also a possibility that by June the majority of these fish will be migrating farther northward if their habitat becomes unfavorably warm around the Bahamas region. ROFFS™ will be monitoring these and other conditions that develop over the next several weeks and months as we do in other areas.

Seasonal Concluding Thoughts…

Based on what we have been observing in March, the present ocean conditions for marlin, yellowfin and blackfin tuna, wahoo and dolphin action in the Bahamas region, particularly in the eastern and northern Bahamas, look excellent. Compared to last year, the conditions this March appear more favorable for early fishing action, and may even be better for mid-spring to late spring fishing action. It is important to note that conditions in the Bahamas region are similar to what they were in 2017, one of the better years for fishing action over the past decade, putting into perspective that this year is also going to be an above average year. The current ocean conditions in the Bahamas suggest that the larger influx of blue marlin, yellowfin tuna and other pelagics may be earlier this year compared to last year. The fishing action this year has the potential to be better than last year during the month of April and May and continue with good fishing conditions into June. Although the rough weather during March prevented many from venturing offshore off Eleuthera and Abaco, we have received reports of a marlin, and multiple wahoo, tuna, and mahi being caught off southeast Florida, and good wahoo action as far north as Cape Hatteras. This suggests a pulse of the “blue marlin water” has likely reach the Gulf Stream. This confirms the start of early good to excellent fishing action in the eastern to northern Bahamas and north along the U.S. Coast. We will continue monitoring these developments as the season progresses and will provide updates when possible.

In conclusion, it is very important to note that good fishing action on a daily basis is strongly linked to local, short-term (24-48 hours) current conditions that concentrate the fish once the preferred habitat of the fish are in a particular region. When the water mass boundaries of these currents are geographically stable and favorable, i.e., continuously pushing over good bottom topography such as the Pocket, Hole in the Wall, or Little Abaco Canyon, then they concentrate the baitfish and larger fish can be found foraging. This means that the fishing action on any given day is controlled by hourly to daily and relatively small-scale (1-5 mile) movements of the currents and their water mass boundaries. Our experience indicates that to reliably forecast specific concentrations of fish on a daily basis, one must evaluate the ocean conditions on these scales. Relatively small subtle changes in the currents and their boundaries often have dramatic effects on the distribution and concentration of fish. Contact ROFFS™ for these daily detailed fishing forecasting analyses and get the inside track to where the better conditions are tomorrow. Get ready now for the spring Bahamas tournaments and other fun fishing action as the excellent fishing conditions in the Bahamas region may have already started.

Stay tuned to ROFFS™ for the next few weeks for additional discussion related to marlin, yellowfin tuna, mahi, wahoo, sailfish and bigeye tuna and oceanographic conditions and seasonal fishing forecasting off the United States east coast and in the Gulf of Mexico area.

Safe and Successful Fishing from ROFFS™